Table of Contents Show

I. The Roots of Determination: Early Life in Poland

In the cold winters of Warsaw, Poland, the seeds of Marie Curie’s relentless pursuit of knowledge were sown. Born Maria Skłodowska on November 7, 1867, she was the youngest of five children in a family beset by hardship but rich in intellectual curiosity. Her father, Władysław Skłodowski, was a teacher of mathematics and physics, and her mother, Bronisława, ran a boarding school for girls. The Skłodowski household was a sanctuary of learning, where the value of education was impressed upon the children despite the oppressive environment of Russian-occupied Poland.

The Skłodowska family’s fortunes were meager, their income insufficient, especially after the death of Bronisława from tuberculosis when Maria was only ten years old. The loss of her mother was a profound blow to young Maria, but it also steeled her resolve. The Skłodowski children were expected to contribute to the family’s sustenance, but Maria’s hunger for knowledge could not be quenched by conventional means. She devoured books, often late into the night, her mind aflame with the ideas that had fueled her father’s teachings.

Despite the restrictions placed on Polish education by the Russian authorities, Maria excelled in her studies. She yearned to continue her education at the university level, but women were barred from attending institutions of higher learning in Poland. Her path seemed blocked, but Maria was not one to yield to circumstances. She found solace in the clandestine “Flying University,” an underground network of educators and students who defied the Russian ban on higher education for women. Here, she honed her intellect and nurtured her dream of becoming a scientist—a dream that would eventually lead her to Paris, the city of light and learning.

II. The Forge of Genius: Paris and the Sorbonne

The journey to Paris was not merely a physical transition; it was a leap into the unknown, a gamble on a future filled with promise and peril. In 1891, Maria Skłodowska became Marie Curie, enrolling at the Sorbonne in a city that was both welcoming and indifferent to her plight. The Paris of the late 19th century was a place where intellectual ambition could be realized, but it was also a city that demanded everything from those who sought its treasures.

Marie arrived with little more than her fierce determination and a small stipend from her father. She lived in a garret, often going without food to save money for her studies. The rigorous demands of the Sorbonne were a crucible that tested the limits of her endurance. Her days were filled with lectures, and her nights were consumed by study. She mastered French, absorbed the principles of physics and mathematics, and began to lay the foundation for the work that would change the world.

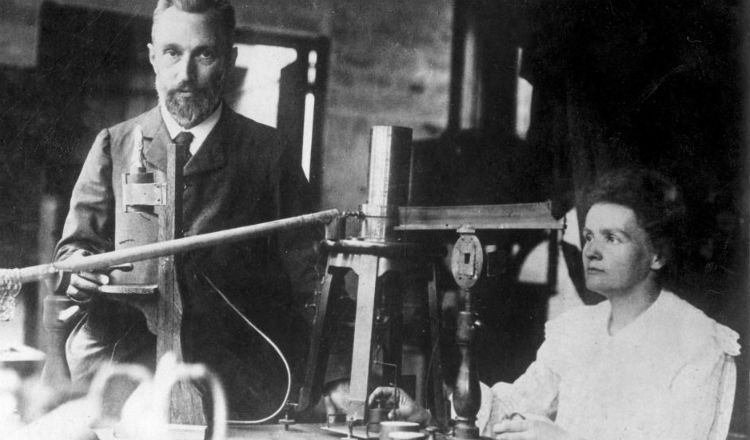

It was in Paris that Marie met Pierre Curie, a physicist whose work on magnetism had already earned him a place among the scientific elite. Pierre was a man of quiet intensity, a scholar whose devotion to science matched Marie’s own. Their partnership was one of equals—an intellectual and emotional alliance that would become the bedrock of their groundbreaking research.

The Curies married in 1895, and their union was more than a personal commitment; it was the merging of two formidable minds. In the laboratory they shared, they began to explore the mysteries of radioactivity, a term that Marie herself coined. Their work was methodical, driven by a shared belief in the power of science to reveal the hidden truths of the natural world.

III. Breaking Through: The Discovery of Radium and Polonium

The discovery that would etch Marie Curie’s name into the annals of history began with a simple observation: certain materials emitted a strange, penetrating energy. Inspired by Henri Becquerel’s work on uranium, Marie decided to investigate this phenomenon further. What began as a routine scientific inquiry soon became an all-consuming quest.

The Curies’ laboratory was a modest space, ill-equipped for the monumental task ahead. But what they lacked in resources, they made up for with ingenuity and sheer determination. They began to meticulously isolate and examine different elements, driven by the belief that there was something new—something fundamental—waiting to be discovered.

Their breakthrough came in 1898 when they identified two new elements: polonium, named after Marie’s beloved Poland, and radium, named for the Latin word for ray. The significance of these discoveries was not immediately apparent, but the Curies understood that they had uncovered something extraordinary. Radium, in particular, was found to emit a powerful energy that defied conventional scientific understanding.

The discovery of radium was a watershed moment, not only for the Curies but for the world. The element’s mysterious energy captivated the public imagination, and soon Marie and Pierre were the focus of intense media attention. Despite the fame, the Curies remained committed to their work, driven by a relentless pursuit of knowledge rather than accolades.

In 1903, Marie Curie became the first woman to win the Nobel Prize in Physics, sharing the honor with Pierre and Henri Becquerel. The recognition was a validation of their groundbreaking work, but it also marked the beginning of new challenges, as the Curies’ research increasingly intersected with the emerging field of medical science.

IV. The Price of Discovery: Tragedy and Triumph

The triumphs of Marie Curie were often shadowed by personal and professional tragedies. The most devastating blow came in 1906 when Pierre Curie was killed in a street accident, leaving Marie to navigate the labyrinth of grief and the responsibilities of raising their two daughters alone. Yet, in the face of overwhelming loss, Marie’s resolve only hardened. She was appointed to Pierre’s chair at the Sorbonne, becoming the first woman to teach at the prestigious institution. Her lectures were a testament to her resilience, her voice unwavering as she carried on the work they had begun together.

Marie’s focus on her research never wavered, even as her health began to deteriorate. The very elements she had discovered were slowly poisoning her, though the dangers of radiation were not fully understood at the time. Despite the physical toll, she continued to push the boundaries of science. In 1911, Marie was awarded a second Nobel Prize, this time in Chemistry, for her work in isolating pure radium. She became the first person to win two Nobel Prizes, a feat that underscored her extraordinary contributions to science.

Yet, with the accolades came scrutiny and scandal. Her personal life was subjected to public examination when her relationship with physicist Paul Langevin, a married man, became the subject of a media frenzy. The scandal threatened to overshadow her scientific achievements, but Marie refused to be cowed by public opinion. She weathered the storm with characteristic stoicism, her focus always on her work and her daughters.

V. The Legacy of a Luminary: Impact and Influence

Marie Curie’s life was a testament to the power of perseverance and the relentless pursuit of knowledge. Her discoveries laid the groundwork for the field of atomic physics and had profound implications for medicine, particularly in the treatment of cancer. The establishment of the Curie Institutes in Paris and Warsaw ensured that her legacy would endure, fostering research that continues to save lives to this day.

Her contributions to science were recognized in her own time, but the true extent of her influence became even more apparent in the decades following her death in 1934. Marie Curie was a trailblazer not only for women in science but for all who seek to expand the boundaries of human understanding. Her work challenged the established norms of her time and opened new avenues for exploration that continue to inspire generations of scientists.

Marie Curie’s life was marked by a series of firsts: the first woman to win a Nobel Prize, the first person to win Nobel Prizes in two different sciences, and the first woman to teach at the Sorbonne. But these accolades, as significant as they are, only tell part of the story. Her true legacy lies in the spirit of inquiry she embodied, the determination to push beyond the known into the realm of the possible. In this, she was not only a pioneer but a beacon for all who follow in her footsteps.